Hoppy Days for Weiss Guys: the IPA-BCs of Microbreweries

The hue of beer glasses tends to mirror the turning of the leaves as autumn begins and beer drinkers move from citrusy whites to heartier IPAs and darker ales. Canadian Thanksgiving may not be as big a day for beer buying as its American counterpart, but many Canadians will sip beer this weekend as they sit with family and gorge themselves on lovingly prepared meals (or talk politics, as the case may be). Some of you might even have opted to buy your favourite craft beer to mark the occasion; microbreweries are a growing institution of the beer industry, after all. This piece is all about the little weiss guys.

The beer industry and the “craft beer revolution”

Beer has a long history – as many as 3900 years! – and has played an important social role across many cultures. But for much of this time the production process of beer didn’t change much, leading scholars to say that a ‘technological plateau’ had been reached. This all changed with the introduction of pasteurization into the beer-making process, which made possible mass production. It was this innovation that laid the groundwork for the rise of large beer companies that have dominated national and, increasingly, global markets. This shift to a large extent still describes the global beer market today. You’ve probably heard of a few of these giants – Anheuser-Busch, SAB Miller, Heineken International and Carlsberg Group.

But this article isn’t about the big guys: it is about the microbreweries that have risen as complements to Big Beer. Microbreweries have, of course, been a longstanding institution of beer production. A microbrewery is just a beer production company that is small in scale, although there are different standards for how small a brewery has to be to count as a microbrewery. Often, microbreweries employ around 4-6 people but there are also many operations (sometimes called “nanobreweries”) that are entirely owned and operated by one person. Although some accounts suggest that the microbrewery trend began in the 1970s, microbreweries really began to shape the beer market in the 1990s, as they successfully built upon a demand for small scale, “craft”, beer.

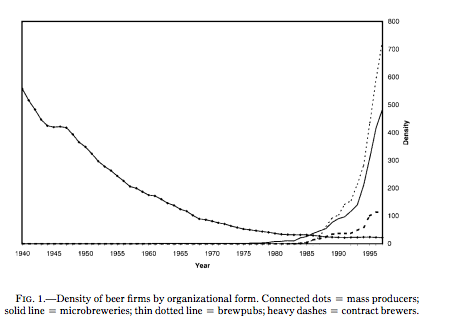

Want to see a nice graph chronicling these changes in the beer industry? Me too! The line going down is mass produced beer, and the lines going up are smaller breweries. It is worth noting that this is the number of firms -- by their nature, a smaller number of big beer firms still produce the vast majority of beer by volume.

Wassup with the growth of microbreweries in the ‘90s?

One explanation for the rise of microbreweries beginning in the 1990s is that the concentration of markets in an industry creates space for specialized groups within that industry. (This is called “resource-partitioning theory”). In a way, the rise of mass-produced beer also created microbreweries.

Fun side note: the U.S. Better Business Bureau's page on the brewing industry has an entire section dedicated to growlers.

We’ve all heard the “hipsters love craft beer” trope. So, it should come as no surprise that scholars have also associated microbreweries and craft beer with social movements arising around that same time. The 1990s was the decade of anti-globalization protests, after all, and craft beer aligned with the localist sentiment accompanying this subculture. Some scholars even suggest that microbrewing is a social movement as well as an industry.

Glob-ale-ization: microbreweries around the world

Microbreweries exist all over the world, but are largely concentrated in wealthy countries. The U.S. is the biggest microbrewery producer. As of 2014 there were 1871 microbreweries and a further 1412 brewpubs in the U.S. alone, accounting for 10% of the $100 billion U.S. beer market. Unsurprisingly, this trend has extended into Canada, America’s hat. There are micro-breweries across all ten Canadian provinces, as well as one in the Yukon. This map shows the 60+ microbreweries in Ontario, which account for around 30% of the brewing industry in that province.

Across Europe, microbreweries account for the huge influx of new breweries over the past five years – the number of European breweries has grown by 73% in that time. Notably, the growth of microbreweries has been uneven in Europe. In some countries microbreweries have exploded: for example, in the U.K. the number of microbreweries doubled between 2001 and 2011. In other places, microbreweries are a smaller trend owing to the resilience of big beer. Most representative of this is Germany. The craft beer revolution has been slow to reach Germany because of its puritan beer culture and its beer law, which limits what can go into beer (based on a Bavarian edict from 1516). But recently, as large German breweries have begun to decline, the number of small breweries in Germany has grown by 25%.

Microbreweries have also emerged outside of North America and Europe. In Japan, for example, there are over 200 microbreweries – a smaller number than some North American and European countries, but still a formidable presence. (Check out this list of the ten best craft breweries in Japan.) The first Thai microbrewery opened in 1999 leading to a rise of craft beer, although it is difficult to estimate its size because many brewers are illegal underground producers. Brazil is also the site of a bourgeoning, but smaller, microbrewery scene, the epicenter of which is São Paulo.

Most microbrewers sell their products primarily to domestic markets because global distribution is expensive (so, for global distribution to be profitable requires greater economies of scale than most such organizations can achieve). But some microbreweries certainly do export their products. In the U.S., for example, craft beer exports increased by 86% between 2010-2011. British microbrewers are also increasingly exporting their product. Still, most microbrews are sold either locally (often in brewpubs) or regionally.

NOTE: this article was inspired by a fantastic presentation given by Giulio Buciuni which compared microbreweries in California and Northeastern Italy. Because this presentation introduced a work-in-progress, I have not included any findings or arguments from the presentation. Nonetheless, credit should be given for introducing me to some of the core concepts included in this piece. You can access more of Giulio’s research here.