Episode 61 - Conflict Minerals

We based this episode on a paper that Kristen wrote a while back, so we thought we’d post the whole thing here!

I. Introduction

Production has globalized: it is organized into complex intra- and inter-firm value chains that span countries, regions, and continents. This new reality has posed challenges because our governance system – which is still based on territorial state sovereignty – places boundaries that are impermeable to regulators while globally networked firms slip through them with relative ease. In reaction to this challenge there has been a rise of transnational advocacy organizations that engage in private politics. These movements aim to get companies to engage in behavior that goes beyond compliance with national laws, often through participation in multi-stakeholder initiatives. From fair trade coffee to sustainable paper and fish, transnational advocacy movements have shaped the contours of global commodity governance. This paper provides an anatomy of one such movement – the Enough Project’s conflict minerals movement, which was a campaign that involved political consumerism (PC), in combination with public politics, to address a global governance challenge. The case study highlights three aspects of transnational advocacy campaigns in global governance: their iterative nature, the importance of inter-firm dynamics in advocacy strategy beyond the selection of firms, and the linkage of private and public politics. This paper illustrates the importance of recognizing these three dimensions using the Enough Project’s conflict minerals campaign as an example. I then explore the meaning and implications of analyzing global PC in iterative campaigns that link public and private politics and ultimately seek to build systems of governance.

II. Literature Review

Private politics describes political competition that addresses a situation of conflict without relying on public authority (Baron 2001). Specific efforts under the heading of private politics are called private political actions (PPAs). PPAs include political consumerism (PC) as well as other tactics like protest, petitions, letter-writing and tactics, such as shareholder proxy proposals or social finance, that target the relationship between businesses and financers (Balsiger 2010). PC entails the participation of consumers as purchasers of goods. Although PC is often presented as an individual act, in many cases it is promoted through specific activist campaigns (Balsiger 2010). This paper studies PC as a subset of advocacy activities, and as such focuses on campaigns that encourage PC behaviors. The two dominant types of PC are boycotts and buycotts.

A boycott campaign is a type of PPA wherein an advocacy organization or movement calls on individuals to refuse to spend money on a product or service, in the hopes of changing specific conditions or practices (adapted from Pezzullo 2011: 125). Boycotts are often effective as a threat (Friedman 1985). Buycott campaigns, in contrast, are PPA campaigns where an advocacy organization asks individuals to spend money on a product or service to reward practices or conditions that the organization supports (adapted from Pezzullo 2011: 125). Boycott and buycott narratives may be used in concert throughout the course of an advocacy campaign. Importantly, however, PC need not necessarily involve either a boycott or a buycott. As the case below shows, “name and shame” and firm differentiation tactics are other means of using PC as a PPA tactic.

Although PC is a subset of private politics, in practice two research communities exist. The first category of approaches treats PC and related campaigns as a domestic political act, while the second emphasizes the global system (globalization in the context of territorially-bounded state sovereignty) as central to explaining private politics.

First, non-global studies on PC have primarily taken one of two perspectives: strategic management and civic participation. Strategic management research has sought to understand which firms are targeted by activists, how (and why) firms respond, and how costly such campaigns are for firms (Gupta and Innes 2014; Lenox and Eesley 2009). Some research under this heading also theorizes about activists’ decision making (such as Lenox and Eesley 2009; Gupta and Innes 2014). Second, civic participation and citizenship research attempts to understand PC as an act of political engagement (Copeland 2013, 2014; Simon 2011; Strømsnes 2009; Stolle et al. 2005).

In general, PC research does not consider private politics as a global phenomenon – something to be explained through reference to the global system. It is often implicit in this research that findings apply to global as well as domestic PPAs, something that is possible because it is assumed that the global system does not matter for the analysis. This is either because private politics is conceptualized as a phenomenon undertaken within a state or because public authorities and institutions do not figure into analysis at all. Although PC research often does not take the “global” into account, there exists a complementary research community on global governance and private politics.

There are at least five perceptible strands of global governance research on private politics. The first strand of research seeks to explain why private politics has become more prominent in recent decades (i.e. Ruggie 2004; Büthe and Mattli 2011; Cutler et al. 1999; Princen and Finger 1994). Second, there is a community of research on the nature of private governance, the purpose of which is to understand the differences and commonalities between public and private governance (Best and Gheciu 2014; Graz & Nölke 2008), as well as how this connects to concepts such as authority (Cutler et al. 1999; Hall 2005; Hall and Bierstecker 2002; Higgot et al. 2000; Hansen & Salskov-Iverson 2008; Green 2014), legitimacy (Thirkell-White 2006), accountability (Whitman 2002), and power. A third area of research analyses the characteristics of various modes of private and hybrid governance, especially certification schemes and clubs (Auld and Cashore 2012; Potoski and Prakash 2013; Vogel 2005; Stehr 2008). Questions include how successful these programs have been (Marx and Cuypers 2010; Vogel 2010; Gulbrandsen 2010; Gullison 2003; Espach 2006; Auld et al. 2008; Newsom et al. 2006) and why particular programs are adopted more successfully than others (Cashore et al. 2004; Pattberg 2007). Fourth is the study of voluntary self-regulation (VSR). There are many types of VSR, but in general these programs all aim to create a mechanism for internalizing social aims in the operational decisions of firms (Khanna & Brouhle 2009). The central research question for the VSR community is why companies go ‘beyond compliance’ with laws and regulations (McWilliams & Siegel 2001; Smith 2009; Potoski & Prakash 2012, 2013; Lyon 2009; Haufler 2009; Brik 2013). The fifth community is transnational activism research, which disentangles the roles, sources of power, and strategies of nongovernmental organizations as it relates to private politics (Haufler 2009; Wong 2012; Gourevitch, Lake, and Stein 2012).

The literature on private politics, and especially PC, is relatively new. Nonetheless, researchers have made significant progress in illuminating four aspects of private politics. First, considerable progress has been made toward understanding which firms are likely to be targeted by PPAs (King and Soule 2007; Lenox and Eesley 2009; Rehbein, Waddock, and Graves 2004; King 2008; Gupta and Innes 2014) and how costly these campaigns are for target firms (Baron and Diermeier 2007; Bartley and Child 2011). Second, we now have a clear sense of the types of VSR, their institutional design, and their relative prevalence (Esrock and Leichty 1998; Capriotti & Moreno 2007; Birth et al. 2008; Khanna and Brouhle 2009; Marx and Cuypers 2010; Lyon 2009). Third, research now identifies the sources of motivation for VSR – win-win opportunities, the specter of regulation, and the threat of sales loss (Bhattacharya et al. 2008; Berens et al. 2007; Berliner and Prakash 2013; Elkington 1998; Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Gunningham, Kagan and Thornton 2003; Kurucz et al. 2008; Lyon 2009; Porter and Kramer 2006; Margolis and Walsh 2003) – and how different market contexts or firm characteristics may influence these motivations (Kemper et al. 2013; McWilliams and Siegel 2001; King et al. 2009; Potoski and Prakash 2012; Haufler 2009; Khanna & Brouhle 2009; Haufler 2009; Brik 2013). Finally, we are beginning to know when consumers are more likely to engage in PC behaviors (Ferrer-Fons and Fraile 2014; Wicks et al. 2014; Shah et al. 2007).

Despite the promising findings described above, the literature is imperfect. Three deficiencies prevent a full understanding of PC campaigns and how they influence global governance. PC campaigns need to be understood as iterative, rather than individual events; transnational business governance interactions (TBGIs) are understudied as a response to PC; and inter-firm dynamics merit further attention.

First, PPAs are often studied in isolation from one another. For instance, Lenox and Eesley (2009) present a model of private environmental campaigns in which decisions by the activist and the firm are all theorized as being based on exogenous characteristics such as visibility, capital, and pollution levels. In this model “threats” and “responses” are treated as independent events rather than as elements of a connected advocacy campaign involving multiple actions and firms. Boycotts, and indeed all PPA, should be viewed as an iterative process in which individual “punishments” and “rewards” consist of just one component. Choices in an existing PC campaign are not only influenced by whether a firm is viewed as “receptive” or “resistant” in general, but also the substance of previously communicated commitments and the dynamics of participation within global public policy networks (GPPNs), if the firm has entered into such arrangements.

Second, and relatedly, inter-firm dynamics are critical to understanding many PC campaigns. Of course, in both the global governance and PC literatures there is some attention to inter-firm dynamics, specifically in the selection of firms that are targeted by such campaigns.[1] However, when it comes to the study of advocacy campaigns there is a problem that PC campaigns are conceptualized in terms of individual “boycott” or “buycott” calls. First, advocacy groups seldom select a single firm to target. More often, entire industries are targeted and companies within that industry are differentiated as the campaign evolves. This is true especially for transnational campaigns that respond to the absence of rules governing the conduct of entire industries or value chains. Coding PC as individual boycott and buycott incidents obscures this element of targeting, as well as the communication dynamics of differentiation that unfold as a campaign is iterated, as the case below shows. Second, PC tactics may not always entail a call for a boycott or buycott by the advocacy organization itself. This could either be because the organization opts for a rhetorical strategy of differentiating firms according to relative progress or because it undertakes an indirect PC campaign – in which direct actions are undertaken by loosely affiliated groups – both of which occur in this case. As such, approaching PC as a series of individual “boycott” or “buycott” events is inadequate to understand the use of this tactic in global advocacy campaigns.

Third, the literature separates public and private politics, viewing PC as a type of private politics that leads to private governance. However, the response of firms to PPAs can also entail public politics. This is especially true for PC campaigns that address global issues, where firms may participate in TBGIs as its response, for instance through participation in rule generation (Haufler 2009). This deficiency is not, of course, limited to the PC literature. In general, TBGIs are understudied (Eberlein et al. 2014), as are the links between private and public governance – although recently there has been a bridge cast between private governance and private politics research, with Green and Auld’s (2016) article on the effects of private authority on regime complexes.

III. Case Study: the Enough Project’s Campaign to End Conflict Minerals

In this section I examine the Enough Project’s conflict minerals PC campaign. The case illustrates how the deficiencies of the existing literature prevent us from understanding the true nature of PC campaigns.

III.A. Background on the Problem of Conflict Minerals

The conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) remains one of the world’s worst active crises (Rosen 26 June 2013; Stearns 2012), having claimed as many as 5.4 million lives since 1996 (Coghlan et al. 2007; BSR May 2010). Numerous groups trade conflict minerals in DRC, including armed rebel groups, local protection units, and government forces (UN Group of Experts 12 December 2013; ISI Emerging Markets Africawire 2 April 2009). Extensive evidence links mineral revenue to the conflict, stifled growth, and human rights violations (United Nations Security Council, 15 November 2012; de Koning 2011; Global Witness 4 May 2016; World Vision 2012; Free the Slaves 2011). Profits from the illicit trade of conflict minerals accounts for up to 95% of revenue for armed groups operating in DRC (Canadian Fair Trade Network 2013). This helps them to sustain their operations. It also provides a strong incentive for these groups to avoid peace and instead retain control over mineral rich areas; mineral wealth is thus a driver of the conflict.

The conflict minerals, often called the “3TGs”, include: tin, tungsten, tantalum, and gold. They also include minerals that are derivatives of the 3TGs, especially cassiterite, wolframite and coltan. 3TG minerals are mainly extracted in the eastern region of DRC, where many mines are controlled by rebel groups. They are extracted in artisanal and small-scale mines by local laborers who are illegally taxed and otherwise exploited by rebel groups in control of the mines (Pue 14 September 2014). They are then sold at local trading houses, then again to exporters, who sell the minerals to smelters and refiners that process the minerals. The processed minerals are then manufactured in consumer products. 3TG minerals are present in many common products including electronics – such as laptops, phones, gaming consoles, and tablets – as well as cars, airplanes, medical devices, lighting and jewelry.

“Conflict” or “blood” minerals are a global governance challenge because they involve complex supply chains that cross multiple borders, and where the consumption of a good by end-users contributes to a public problem in another country. As well, due to the lack of state control in DRC, cross-border smuggling of minerals is frequent (Cook 20 July 2012). As such, curtaining conflict minerals requires action across the entire Great Lakes Region (GLR) of Africa. Because 3TGs cross borders and regions multiple times throughout the value chain, governing conflict minerals is as much about influencing smelters in China as it is about wresting control of mines in DRC from armed groups or changing the behavior of multinational electronics giants. Adding further complexity, a development challenge is embedded in the responses to conflict minerals: simply ceasing to purchase 3TGs from DRC and surrounding areas would not solve, but might in fact worsen, development outcomes.

III.B. The Early Movement Against Conflict Minerals

Concern about the problem of conflict minerals first came to public attention in January 2001 when the United Nations appointed a Panel of Experts (UN PoE) to investigate the illegal exploitation of minerals and other resources in DRC. The UN PoE delivered its first report to the Security Council in April 2001, recommending an immediate embargo of trade in minerals from eastern DRC (UN PoE April 2001; Radley 19 April 2016). Between 2001 and 2003 the UN PoE continued to highlight the connection between international business and the conflict (Taka 2016).

Early consumer movements focused on coltan because in 2000 exploding demand driven by cellphones had dramatically increased its price, which then led to mining in rebel-controlled areas of DRC on an unprecedented scale (Haye and Burge 2003). In reaction to the destruction of gorilla habitats as a byproduct of coltan trading, gorilla conservationists, as well as celebrities such as Leonardo DiCaprio, called for a boycott of “blood coltan” in 2003 (Raghavan 7 December 2003). This movement identified the electronics industry, especially cellphone producers, as targets. That same year the Global e-Sustainability Initiative (GeSI), a business coalition, commissioned a study on conflict minerals (Haye and Burge 2003).

Between 2003 and 2005 the UNSC passed resolutions to control illegal mining, but this approach failed to solve the problem (Reinecke and Ansari 2016). The UN Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo (UN GoE) was established in 2004 to support the UNSC’s work. It has produced two reports annually since that time. In 2009 the UNSC formally recognized that conflict minerals were strengthening armed groups in DRC (Africa Review 10 January 2014). Around that time activists had began drawing attention to the culpability of businesses and consumers for conflict minerals. Global Witness, for instance, wrote to 200 companies for a report that it released in 2009. It found that most of these 200 companies had no processes in place to stop conflict minerals from entering the supply chain (ISI Emerging Markets Africawire 22 July 2009). Although policymakers and activists had made clear the connection between minerals and the conflict in DRC at the turn of the millennium, consumer awareness about conflict minerals was extremely low in 2008 (Reinecke and Ansari 2016). It was in this context that the Enough Project’s campaign began.

III.C. The Enough Project Electronics Campaign

The Enough Project is a nonprofit organization based out of Washington, D.C., founded by John Prendergast and Gayle Smith in 2007. Enough’s mission is to end genocide and crimes against humanity. It calls itself “an atrocity prevention policy group” (Enough 17 December 2015). Enough seeks to achieve its goal through a combination of research and mobilization support.

Enough began advocating on conflict minerals in 2009 by writing letters, co-signed with over 30 Congolese and international NGOs, to 21 consumer electronics companies (Enough Project December 2010). The letters called attention to conflict minerals and inquired about the steps that companies were taking.[2] Enough took on an approach in which its main functions were monitoring through research and analysis, as well as support for grassroots activism. As such, it carried out a PC campaign indirectly.

Enough’s monitoring role was threefold. First, Enough produced research through site visits and stakeholder interviews. This research bolstered the organization’s credibility as an expert on conflict minerals and the conflict in DRC, including by embedding Enough within the policy network. It also helped to direct Enough’s policy positions. In addition to research, Enough set a clear advocacy direction – trace, audit, certify – that established coherence across the movement. Third, Enough identified feasible yet ambitious changes for which activists could advocate. It drew on research to constantly modify these recommendations to match unfolding practice.

Alongside its monitoring role Enough has supported other activist organizations, especially grassroots movements, to mobilize on conflict minerals. These activities consist of coordination and capacity building functions, as well as amplifying activist messages and awareness raising. One initiative falling under this category is the Raise Hope for Congo (RHC) campaign. Through RHC Enough sought to build a “permanent and diverse constituency of activists” advocating for human rights in DRC (Enough n.d.). In its mobilization efforts, Enough has sought to encourage multiple simultaneous actions targeted at different actor groups. Enough devoted its early mobilization efforts to raising consumer awareness. For instance, in 2010 Enough produced a satirical video modeled on Apple’s “Get a Mac” ads.[3] The video was shared by major news outlets and tech writers (i.e.: Smith and Prendergast 28 June 2010; Kristof 26 June 2010; VanHemert 28 June 2010; Computerworld 27 June 2010; Crocker 27 June 2010). In 2009 Enough was featured alongside Human Rights Watch in a “60 Minutes” segment on conflict minerals.

III.C.1. Rewarding Leaders, Shaming Laggards

Enough targeted companies at the top of the supply chain, asking them to use their buying power to influence suppliers. Specifically, it identified major electronics producers, utilizing a strategy whereby it compared companies against one another. The campaign used communication techniques that simultaneously rewarded some companies for leadership and criticized others for lack of progress, while stressing the tangible steps that all companies could take to continue improving.

A report by Prendergast and Lezhnev (2009) provided detail on the six steps in the 3TG supply chain for electronics, arguing that the supply chain was not so complex as to be impossible to govern. That same report included three behaviors that it asked consumers to demand. Specifically, electronics producers should: trace their supply chains; conduct third party audits; and purchase third-party certified conflict-free minerals from the region (Prendergast and Lezhnev 2009). In February 2009, Enough and other human rights groups demanded that 21 major American electronics producers sign a pledge to do so (ISI Emerging Markets Africawire 16 May 2009).

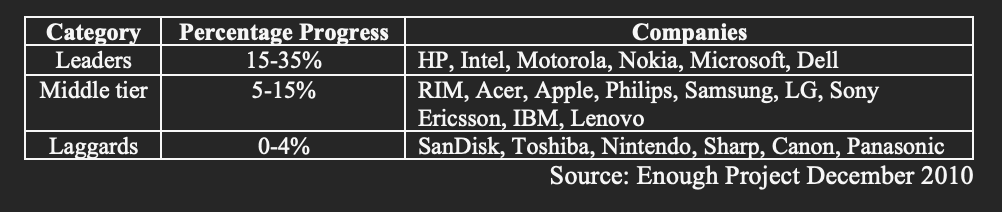

In 2010 Enough ranked 21 electronics companies’ progress on conflict minerals. The rankings were intended “to provide consumers with the information they need to purchase responsibly” (Enough Project December 2010: 2). Companies were ranked on 18 criteria, spread over five categories: tracing, auditing, certification, legislative support, and stakeholder engagement (Enough Project December 2010). Enough rewarded six companies by designating them as leaders, punished six companies by designating them as laggards, and identified a middle tier of nine companies. The progress meter that Enough used underlined that all companies had considerable space to improve, while acknowledging leadership by individual firms. The report that accompanied the rankings offered specific suggestions that firms could enact, individually and through industry groups, to improve (Enough Project December 2010). The rankings were reported on by news outlets (Khan 7 January 2011; Ethical Living 2010) and used in Enough’s communications.

In 2011 Enough shifted emphasis to encouraging a certification system for 3TG minerals in the GLR (Prendergast, Bafilemba, and Benner February 2011). This shift partially reflected increased acceptance of responsibility on the part of major electronics producers for tracing and auditing (see section III.F). In part, it occurred in response to new US legislation, which created a public disclosure mechanism to encourage tracing and auditing – while work on a certification system was far less developed (Lezhnev and Sullivan May 2011). Because transparency had been an issue for early industry initiatives (Enough Project December 2010), Enough also emphasized that the certification scheme would need to be transparent, multi-stakeholder governed, third-party audited, and should involve penalties for noncompliance (Lezhnev and Sullivan May 2011)

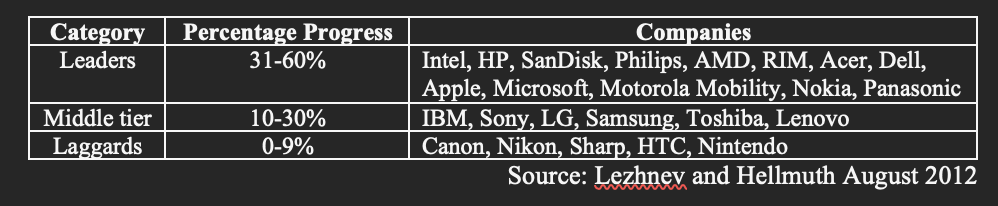

Enough released its second set of company rankings in 2012 (Lezhnev and Hellmuth August 2012). These rankings used a similar methodology to rank 24 electronics companies on their progress toward responsible sourcing of the 3TGs. Enough increased the threshold required to be designated as a “leader”. It rewarded 13 companies by designating them as leaders and lauded Intel and HP for standing “ahead of the pack” (Lezhnev and Hellmuth August 2012: 5). It also recognized six companies – SanDisk, Philips, Sony, Panasonic, RIM, and AMD – for “significantly improved” efforts (Lezhnev and Hellmuth August 2012: 1). The progress meter in the report included benchmarks for the progress that companies had made since 2010. Enough also punished five companies by designating them as laggards. In contrast to the first rankings, where four companies had made no progress at all in addressing conflict minerals, only Nintendo had a 0% progress ranking in 2012.

The report that accompanied the rankings identified five gaps companies should address (Lezhnev and Hellmuth August 2012). It also included a sizable section on other industries that use 3TGs, framing these industries as generally inactive but rewarding several companies that have taken steps on conflict minerals. Again, newspapers and other major media outlets reported on the rankings (Reuters 15 August 2012; Meger 31 August 2012; Kaufman 12 January 2016; Miller 16 August 2012).

Enough has not produced an electronics company ranking since 2012. However, in its reports it continues to reward companies for showing leadership (Bafilemba, Mueller, and Lezhnev June 2014; Dranginis 24 November 2014; Hall and Lezhnev 11 November 2013).

Enough bolstered its credibility by producing reports that drew on site visits and interviews. These reports detailed human rights abuses in DRC (Dranginis 21 January 2015; Lezhnev 27 October 2016), the connection between minerals trading and the conflict (Lezhnev and Sullivan May 2011; Enough Project October 2012; de Koning and the Enough Project October 2013), policy challenges to addressing conflict minerals (Fenwick 30 August 2012), and the effect of ongoing efforts (Bafilemba, Mueller, and Lezhnev June 2014). The reports frequently cite the UN GoE, as well as Global Witness, Human Rights Watch, Congolese civil society groups,[4] and other credible experts.

III.C.2. An Indirect PC Strategy

PC was a key element of Enough’s campaign. Many of their communications mention “consumer pressure” as the mechanism compelling companies to act. For instance, Jonathan Hutson at Enough has said: “Apple is claiming that their products don’t contain conflict minerals because their suppliers say so. People are saying that answer is not good enough. That’s why there’s this grass-roots movement, so that we as consumers can choose to buy conflict free.” (cited in Kristof 30 June 2010). In 2009 another Enough representative said: “As long as we don’t change the way we go about purchasing these things economic incentives will override [the need for supply chain transparency]” (David Sullivan, cited in ISI Emerging Markets Africawire 22 July 2009). Moreover, Enough’s reports and rankings point responsible consumers to certain companies instead of others. It has also asked consumers to tell industry leaders to act on conflict minerals, for instance through its Change the Equation for Congo five-day social media campaign that targeted each of Apple, Nintendo, Intel, BlackBerry, and Dell for one day (Take Part 9 December 2015).

However, Enough largely relied on local activist groups to undertake direct PPAs. Enough has supported the mobilization of these PC campaigns. Recall the RHC campaign discussed above. Through RHC Enough has eight DRC partners, including advocacy networks and service provider charities. Enough also has twenty American and international partners through RHC, including major international NGOs like Human Rights Watch, Oxfam, and Amnesty International. Enough’s Conflict-free Cities initiative, which is a component of RHC, encourages activists to ask their city governments to pass resolutions committing to insist upon conflict-free standards in their major purchasing contracts. Conflict-free resolutions have been passed in five American cities and Kingston-Upon-Hull, which is in the UK (Enough 26 August 2015).

The Conflict-free Campus Initiative (CFCI) is another project nested within RHC. Through CFCI Enough supports groups at universities and high schools – primarily in the US and Canada but also elsewhere – that are working to eliminate conflict minerals on their campuses.[5] Enough provides student groups with informational resources, guidance, and a web platform through which to promote calls for action (i.e. petitions and letter-writing campaigns). Enough also holds training sessions and conferences, bi-weekly calls with their Coordinator, and virtual sessions in which student groups could interact (Callaway 12 May 2016). CFCI actions often seek to change university policies,[6] but also involve awareness raising and actions targeted at governments and companies. For instance, Conflict-free Duke sent a video message to Apple CEO Tim Cook (Jones 27 January 2012). In another case activists flooded Intel’s Facebook page calling on it to support US conflict minerals legislation (Kristof 29 June 2010).

Activists have also circulated online petitions echoing Enough’s suggested advocacy goals, for example the change.org petition by Congolese activist Delly Mawazo Sesete that called on Apple to make a conflict-free product that includes minerals from DRC.[7]

III.D. Hybrid and Private Initiatives

Enough promoted company engagement in initiatives to encourage in-region conflict-free minerals, although it has also criticized these same initiatives for their failings. Specifically, the following industry initiatives have been mentioned in Enough’s communications: the Conflict-Free Sourcing Initiative (CFSI) and its Conflict-Free Smelter (CFS) program; the ITRI Supply Chain Initiative (iTSCi); the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) certification program; and capacity building programs.

III.D.1. Downstream Certification: the Conflict-Free Sourcing Initiative

The EICC and GeSI have worked together on conflict minerals through what became CFSI.[8] Initially known as the EICC-GeSI Extractives Working Group, this group was replaced by CFSI in 2013. CFSI puts systems in place so that downstream producers can influence their suppliers to be conflict-free. It has created a standardized reporting template, which helps downstream producers to gain information about its suppliers. The current version of the reporting template is tailored to the US conflict minerals law. CFSI also publishes lists of active and compliant smelters and refiners,[9] based on CFS. CFS was developed by EICC-GeSI in 2009. It is a third-party audited system for validating compliance with protocols developed to meet international standards on due diligence for conflict minerals (CFSI 16 July 2012). To be CFS-certified the smelter must show documentation that can determine with reasonable confidence that the minerals it processed originated from DRC conflict-free sources (CFSI 12 September 2015). Enough encouraged participation in EICC-GeSI as part of its campaign (Enough December 2010). However, it also pressed the group to take meaningful action (Enough Project December 2010). “We were concerned that this industry-wide approach allowed companies who were not interested in taking action to hide behind the association” (Sullivan 1 December 2015).

III.D.2. Upstream Certification: the ITRI Supply Chain Initiative

iTSCi is a third-party audited upstream certification system operating in DRC and Rwanda. It is a system for tracing the origin of 3T minerals from mine to smelter that was started in 2009 by ITRI, which is a tin industry organization (Van der Linde 3 February 2011). iTSCi initially certified only tin mines but has since expanded to include tantalum and tungsten mines as well. The program operates at around 1000 mine sites in Burundi, Rwanda, and DRC (ITRI n.d.). Enough has encouraged the creation and expansion of iTSCi (Lezhnev and Bafilemba 13 March 2014) but has also pressed for the system to be improved, for instance by eliminating loopholes and improving transparency (Bafilemba, Lezhnev, and Zingg-Wimmer August 2012).

III.D.3. The International Conference on the Great Lakes Region

ICGLR is an international organization comprised of twelve Central African member states. It was created in 2000 to improve peace and security in the region (ICGLR n.d.). ICGLR began planning a certification system for conflict-free minerals in 2010 (Partnership Africa Canada June 2012). The ICGLR Regional Certification Mechanism addresses all four 3TGs. It is an upstream system with four components: mine inspections and traceability; an information database; audits; and independent monitoring. The first ICGLR certificate was issued in November 2013 in Rwanda. However, this was before all components of the program were in place. As Enough has pointed out, the Audit Committee and Independent Mineral Chain Auditor had not been appointed (Hall and Lezhnev November 2013). Enough has asked US envoys to work with ICGLR to finalize that organization’s certification process (de Koning and the Enough Project October 2013; Hall and Lezhnev November 2013). While Enough supports ICGLR, it has continued to stress that the framework needs to improve (Bafilemba, Mueller, and Lezhev June 2014).

III.D.4. Capacity-building Initiatives

Several capacity-building initiatives have developed to support conflict-free minerals in the GLR since 2008. Some notable examples include: the Public-Private Alliance on Responsible Minerals Trade (PPARMT), Solutions for Hope (SfH), and the Conflict-Free Tin Initiative (CFTI). Enough has encouraged participation in these initiatives in its campaign communications.

PPARMT is a multi-sectoral initiative with participation from INGOs, USAID and the State Department, the ICGLR, and companies (including electronics companies). It was launched in 2011 and formalized in a 2012 memorandum of understanding (PPARMT August 2012). PPARMT provides funding and coordination support to organizations working within the GLR to promote conflict-free capacity for industry, civil society, and governments (Resolv 2016). Enough is a participant in PPARMT and has encouraged membership in PPARMT (Lezhnev and Hellmuth August 2011, 2012; Lezhnev and Sullivan May 2011; de Koning and the Enough Project October 2013).

SfH was initiated by Motorola Solutions in 2011. The purpose is to create and test a program of responsible sourcing from the DRC. Under the thinking that setting up conflict-free infrastructure required defined end-users, SfH defined a set of rules and players to demonstrate that companies could source conflict-free tantalum from DRC while meeting due diligence requirements (RESOLVE 30 October 2014; Motorola Solutions 2012). In 2014 the Motorola Solutions Foundation announced a grant to RESOLVE to help expand SfH within DRC and in surrounding countries (Motorola Solutions 28 October 2014). Enough has supported this initiative, pointing out its benefits for Congolese miners (Bafilemba, Mueller, and Lezhnev June 2014: 17; Enough 13 March 2014).

CFTI began in 2012 as a partnership between Philips and the Netherlands (Philips updated 2016). Similar to SfH, CFTI sought to demonstrate that it was possible to source conflict-free tin from DRC (RESOLVE 2014).[10] It concluded in 2014. Upon the establishment of CFTI, Enough said: “this joint initiative [CFTI] is showing leadership by sourcing minerals from a conflict-free mine in eastern Congo” (Sasha Lezhnev, cited in RESOLVE 18 September 2012). However, Enough has been careful to stress that pilot initiatives like CFTI are insufficient by themselves. “This project [CFTI] is a positive step but should be followed up with a permanent independent monitoring system to ensure no conflict minerals leak into the system” (Enough 26 February 2013).

III.E. Public Politics

As it was pursuing a PC campaign, Enough was also involved with public politics at several levels. Domestically, Enough has advocated for conflict minerals legislation in the US and elsewhere. It has also advocated for the US government to use its foreign policy tools, including development funding, to address the problem of conflict minerals. Internationally, Enough has participated in processes at the United Nations, the OECD, and ICGLR, as well as other lower profile multi-stakeholder initiatives involving public actors. Throughout, Enough has connected its private and public political actions by encouraging companies to participate in public political processes. This section discusses Enough’s involvement with public policy on conflict minerals.

III.E.1. The OECD Due Diligence Guidance

The OECD’s Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (OECD DDG) was issued in March 2011 and endorsed by the OECD in May 2011. It defines an approach to implementing due diligence for conflict minerals (OECD January 2013), and is a reference point for international efforts to curtail the trade in conflict minerals. The OECD DDG was developed through a multi-stakeholder process engaging governments, industry, civil society, and the United Nations. Following the endorsement of the OECD DDG Enough partnered with other human rights NGOs to call for companies to begin implementing these standards (Enough 27 May 2011).

III.E.2. The Dodd-Frank Act Conflict Minerals Rule

A major milestone was achieved when the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) was passed in 2010. The Dodd-Frank Act included a conflict minerals provision, s.1502, which required companies that use 3TG minerals in production to report on its due diligence practices publicly to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Enough had advocated for the creation of this provision by lobbying government officials and producing research and analysis on why the law would be useful. In addition to these tactics of “public politics”, Enough encouraged major electronics producers to publicly support the conflict minerals provision through statements of support. Intel, for instance, was targeted on its Facebook page for failing to publicly support the rule (Rogoway 26 June 2010). Enough has been explicit about the connection between its public advocacy on Dodd-Frank Act s.1502 and its PPA: “Dodd-Frank has been necessary to bring in the over 1,000 companies with weaker leadership and which are not as sensitive to consumer pressure” (Bafilemba, Mueller, and Lezhnev June 2014: 7).

After the rule was established in law Enough again engaged in both public and private politics to ensure the implementation of the rule. The SEC received “some 13,000 letters urging it to promptly adopt this rule” (Business Daily 10 January 2014) due to activist mobilization. As to private politics: after the Dodd-Frank Act was passed there was initially some debate about how s.1502 would be implemented. Amid this debate Enough continued to call on companies to speak in support of s.1502 and to participate in policy processes about how to implement the provision (Enough 27 June 2012).

In June 2012, Enough and an amalgam of human rights groups called on companies to publicly express support for s.1502 and against the US Chamber of Commerce, which was suing the SEC. PC was invoked as an argument in that debate, notably by the Executive Director of Jewish World Watch. He said:

Consumers have made it plain to companies that they want conflict-free products to come to market, and stand ready to reward those companies that are doing their utmost to achieve that goal. […] Those same consumers will be sorely disappointed to learn that otherwise proactive companies are at the same time hedging their bets by quietly supporting the Chamber. (Fred Kramer, cited by Global Witness 27 June 2012).

In August 2012, the SEC introduced its ruling implementing s.1502 (SEC 22 August 2012). While the SEC rule provided some clarity as to the requirements of s.1502 companies retained considerable leeway – first, because the requirements were largely procedural and, second, because there were some aspects that remained open for interpretation. Enough sought to shape how companies responded to these new legislative requirements. Specifically, Enough and the Responsible Sourcing Network (RSN) co-produced a report on the content that they expected to see in companies’ disclosures:

SRIs [socially responsible investors] and NGOs will look poorly upon issuers that postpone robust reporting or file a report that simply ticks a box. Conversely, stakeholders will publicly acknowledge issuers that actively demonstrate efforts to address the issue, provide transparent procedures and results, and make progress over time […] the extent to which an issuer takes a holistic approach to supporting a clean minerals trade in the DRC will be noted and rewarded. (Fenwick and Jurewicz September 2013: 2)

Since its implementation Dodd-Frank Act s.1502 has been criticized because the disclosures do not contain enough information to determine which companies are acting responsibly and for the effect that the legislation has had on mining in the GLR (Karubanga 22 November 2015). Reform of the conflict minerals provision is currently being considered (Just Means 8 November 2016), particularly in light of the low number, about five percent, of reporting companies that have been able (or willing) to meet the requirements (King 5 June 2014).

III.E.3. Other Conflict Minerals Legislation

The United States is the only country outside of the GLR to have enacted a law requiring disclosure of conflict mineral due diligence. However, legislation has been debated in both the European Union (EU) and Canada.

The EU began work on conflict minerals legislation in 2013, but as yet the process is ongoing. Enough signed, with 57 other civil society organizations, a position paper calling on the European Commission (EC) to adopt mandatory legislation (Civil Society Position Paper 16 September 2013). In May 2015, the European Parliament (EP) voted to reject the EC’s proposal of a voluntary self-certification system, instead requesting that the regulation be mandatory (20 May 2015). After some discussion, the EP’s negotiators reached a provisional agreement with the Council of the EU on mandatory reporting for upstream companies and voluntary disclosures for downstream companies (Gardner 16 June 2016). New draft regulation has yet to be ratified by the EP (EurActiv 8 November 2016).

Canada has introduced two draft conflict minerals bills. However, both were bills introduced by an opposition Member of Parliament (MP), which are exceedingly unlikely to pass. In 2010 then-MP Paul Dewar, the New Democratic Party’s foreign affairs critic, tabled Bill C-571 (Klaszus 13 December 2010). Bill C-571 was not voted on due to an election. Paul Dewar reintroduced the legislation as Bill C-486 in March 2013. It failed on 24 September 2014. Enough promoted Bill C-486 and an affiliated petition through CFCI (Callaway 16 September 2014; Conflict-Free Campus Initiative 3 May 2013), and indirectly by promoting the activities of STAND Canada and other advocacy organizations participating in the Just Minerals Campaign. It had previously called on Research in Motion to publicly support Bill C-571 (Enough Project December 2010).

III.E.4. Traditional Diplomatic Tools

Enough has also asked the US government to exercise traditional diplomatic tools to address the problem of conflict minerals, for instance through pressing governments in the GLR or introducing UNSC sanctions (de Koning and the Enough Project October 2013; Hall and Lezhnev November 2013; Bafilemba and Lezhnev April 2015). This area of public political campaigning tended not to also include a private politics component.

III.F. Company Responses

This section discusses the responses of electronics companies. It is organized in accordance with Enough’s four categorizations of companies: early leaders, late leaders, middle performers, and laggards.

III.F.1. The Early Leaders

The “early leaders” are those that Enough recognized in both its 2010 and 2012 company rankings as leading industry efforts: Intel, Hewlett-Packard (HP), Motorola Mobility, Motorola Solutions, Nokia, Microsoft, Dell, and Advanced Micro Devices (AMD). In particular, Intel and HP have consistently sought to be at the frontier of action on conflict minerals. As Sasha Lezhnev has said: “HP and Intel have gone above and beyond the call of duty” (Enough 16 August 2012).

Intel began to act on conflict minerals in 2009 by appointing Carolyn Duran to lead a conflict minerals team (Weekend Argus 1 June 2014). The company faced initial difficulty in tracing their supply chain due to lack of interest from smelters (Weekend Argus 1 June 2014). “A smelter’s decision to participate is primarily based on their customers’ demands. The end goal, which Intel has demonstrated, is getting the smelters convinced that participating in the program and being audited is good for their business” (Carolyn Duran, cited in Weekend Argus 1 June 2014). It took two years for Intel to begin seeing results (Weekend Argus 1 June 2014). Intel met with company representatives (Enough December 2010) and travelled to its suppliers. It has also provided financial support to smelters to pay for audits (King 5 June 2014). In January 2014 CEO Krzanich declared that Intel had made its processors conflict-free (Africa Review 10 January 2014), an achievement for which Enough praised the company (Callaway 1 June 2015). “We felt an obligation to implement changes in our supply chain” (CEO Brian Krzanich, cited in Africa Review 10 January 2014).

However, Enough and the activists that it supports have been willing to criticize Intel. For instance, in 2010 Intel reportedly opposed US conflict minerals legislation, although it never publicly took a position (Rogoway 26 June 2010). Activists flooded Intel’s Facebook page calling on it to act (Kristof 29 June 2010). Though Intel did not publicly support the creation of the conflict minerals provision, it did sign onto a 2012 multi-stakeholder letter on the legal challenge to the SEC’s rule. Intel has also been active in participating in global governance efforts. It co-chaired the EICC-GeSI Extractives Working Group; chaired the review committee for CFS; co-founded, with HP and General Electric, the Initial Audit Fund; and participated in PPARMT and SfH.

HP is the second company that Enough consistently pointed to as a leader in conflict minerals action. However, the approaches that these two companies have taken are somewhat different. While Intel broke ground through its conflict-free microprocessors, HP showed more consistent leadership in American public politics on conflict minerals. Both companies have been active participants in TBGIs.

HP is one of the front-runners in terms of achieving a conflict-free supply chain. The company has set the expectation that its suppliers obtain information on their supply chains and provide that information using CFSI’s reporting template (HP 19 July 2013, 26 May 2016). HP was one of the first three electronics companies to publish its list of smelters, with SanDisk in 2013 and behind Philips in 2012 (Hardy 15 April 2013). HP has not made as much progress as Apple with its smelters and refiners, but it is closer than most. As of April 2015, 59% (152) of the smelters and refiners in HP’s supply chain are CFS compliant, compared with 30% in January 2014 (HP 2016). “The smelters are the chokepoint. Once you locate them, you can start to pressure them to set a standard. […] It took a while to identify all of the smelters, but putting pressure on them is relatively easy.” (Tony Prophet, then-HP executive, cited in Hardy 15 April 2013). As with Intel, HP has found that in-person visits have been the best way to convince smelters to participate in conflict-free programs. HP’s head of conflict-minerals compliance, Jay Celorie, has said: “A smelter’s decision to participate is primarily based on their customers’ demands,” (cited in King 5 June 2014).

Compared with Intel, HP was a more consistent public ally to conflict-free activists that sought US legislation. The company took a stance in favor of Dodd-Frank Act s.1502, and Enough has rewarded this decision in its communications (Hall 22 August 2011). HP also signed onto the 2012 multi-stakeholder letter. However, as Global Witness publicly pointed out, HP’s ties to the US Chamber of Commerce – which sued the SEC over the conflict minerals rule – allow for the potential that the company has tried to “have it both ways” (Global Witness May 2012). In its reply to Global Witness, HP reiterated its public support for the legislation (HP 22 May 2012).

Like Intel, HP has been involved in industry and multi-stakeholder initiatives to establish regulation and governance infrastructure on conflict minerals. HP co-chaired the EICC-GeSI Extractives Working Group; participated in the ICGLR-OECD-UN GoE annual Forum on Responsible Mineral Supply Chains; disclosed its participation in an OECD DDG implementation pilot; is on the governance committee of PPARMT; has, according to Enough, been the “most active participant in a diplomacy working group” on DRC (according to Lezhnev and Hellmuth August 2012: 5); and engages with SfH and CFTI.

Aside from HP and Intel, there are five other companies that Enough has cited as industry leaders from the early stages of the campaign: Motorola,[11] Nokia, Dell, Microsoft, and AMD. These companies have taken individual steps to address their supply chains; have supported human rights groups on public policy to do with conflict minerals; and have engaged in efforts to develop conflict-free governance both in and out of region.

Early leaders have accepted a duty to be active with suppliers to ensure that they are sourcing conflict-free minerals. “[We] have an obligation to do our part, which we fully accept.” (Motorola, cited in Enough December 2010). In 2009 Intel, HP, Dell, and Motorola organized a multi-industry forum to help companies seeking to map their supply chains and implement conflict-free policies (Arbogast 25 August 2009). The early leaders have followed the recognition of responsibility with policies and supply chain mapping.

Several of the early leaders have pioneered initiatives to support systems for regulating conflict minerals in supply chains or building capacity for in-region conflict-free minerals. Motorola Solutions, for instance, created SfH. Early leaders have also been actively involved in the implementation of the OECD DDG, for example by attending the annual ICGLR-OECD-UN GoE Forum. Motorola Solutions’ Mike Loch has given presentations at this forum on several occasions.

Regarding public politics, Microsoft, AMD, and Dell have also supported conflict minerals legislation. Although AMD was not included in Enough’s initial rankings due to its size, it received an honorable mention in the accompanying report because it had leant its voice in support of conflict minerals legislation (Enough December 2010). Microsoft, AMD, Dell, and Motorola Solutions issued statements and/or signed onto a multi-stakeholder letter criticizing the US Chamber of Commerce lawsuit against the SEC. Microsoft has been particularly vocal on conflict minerals legislation. In reply to Global Witness’ May 2012 letter questioning whether companies were trying to “have it both ways” (discussed above), Microsoft was one of few electronics companies to generate a formal reply. In it, Sr. Director of Corporate Citizenship Dan Bross said:

We have publicly supported adoption of these [SEC] regulations, and indeed we have joined human rights advocates in a public comment letter urging the SEC to adopt the regulations without delay. […] On other issues, notably climate change and conflict minerals, we are opposed to the Chamber’s positions and do not fund or support their work. (Bross 22 May 2012).

AMD has been perhaps the most active company in supporting human rights organizations in their public political actions on conflict minerals. AMD and Enough co-chaired a multi-stakeholder policy and diplomacy working group that delivered consensus policy positions to the SEC (AMD 2011). The company also met with Enough and US State Department officials to emphasize the need for government support of in-region sourcing (AMD 2011).

III.F.2. The Late Leaders

The “late leaders” were identified only in Enough’s 2012 report as taking significant efforts to combat conflict minerals: SanDisk, Philips, RIM, Acer, Apple, and Panasonic. In most cases these companies significantly improved their practices between 2010 and 2012, according to Enough.

The companies in this category have participated in initiatives to strengthen governance systems and in-region conflict-free programs. Some, notably Philips, also supported advocacy for conflict minerals legislation. Additionally, the late leading companies have made considerable strides in their supply chain policies, beginning by studying their supply chains. Philips was the first company to publish the names of its smelters and to initiate audits of its suppliers that use the 3TG minerals (Lezhnev and Hellmuth August 2012). SanDisk, Acer, Panasonic, and Apple have since followed suit.

Unlike companies that have taken the lead on capacity-building initiatives and in public lobbying, Apple has focused its energy on its supplier relations. Recently Apple has taken a particularly robust approach to removing conflict from its supply chain. “[W]e believe that participation in third-party audit programs alone is not enough. Ongoing engagement is critical, because some smelters that have completed third-party audits have minerals that are supplied by mines allegedly involved with armed groups.” (Apple 2016: 13) In 2014 the company imposed a deadline requiring its suppliers to become compliant by the end of that year (Apple 2015). As of December 2015, Apple reports that all of its 242 smelters and refiners for the 3TG minerals are subject to third-party audits, an increase from 88% at the end of 2014 and 44% at the end of 2013 (Chasan 30 March 2016; Apple 2016). This strategy has earned Apple praise from Enough and other human rights groups. Enough rewarded Apple for turning around its approach in 2013 (Lezhnev 15 February 2013). Praise accelerated in 2016 (Oboth 11 April 2016). For example, Sasha Lezhnev said:

Apple's new supplier report is a model for how companies should be addressing conflict minerals. Apple's tough love with its suppliers is critical to solving the problem of deadly conflict minerals -- it offered assistance to suppliers but then took the difficult step of cutting out those who were unwilling to undergo an audit. Firm but fair follow-through by tech and other companies with their suppliers is a key step that's needed to cut off global markets for conflict minerals (Enough 31 March 2016).

III.F.3. The Middle Performers and Laggards

The “middle performers” were identified neither as leaders nor laggards by Enough in 2012: IBM, Sony, LG, Samsung, Toshiba, and Lenovo. These companies generally have not supported human rights groups in their public political engagement on conflict minerals and have not led industry or multi-stakeholder initiatives.[12] Middle performers have sometimes participated in groups like PPART. They may also have provided training or support for existing initiatives, for instance through IBM’s technology donation to iTSCi (Chegar 2012). More often, however, these middle performing companies have focused on internal activities. Some, such as Toshiba, have policies requiring all suppliers to work with the company in procuring conflict-free minerals (Toshiba 2016). Others, like LG, have mapped and identified the smelters in their supply chain (LG 2016). The middle performing companies have received little attention in Enough communications, aside from the rankings themselves.

The “laggards” have received a bit more attention from Enough. Laggards are those companies that Enough criticized for having taken the least significant steps in addressing conflict minerals: Canon, Nikon, Sharp, HTC, and Nintendo. These companies have done nothing or very little to address conflict minerals. For instance, after the 2012 rankings came out Nintendo released a statement in which it referred to its corporate social responsibility (CSR) procurement policy. Enough responded strongly to this statement:

Nintendo's statement is a meaningless piece of paper without concrete steps behind it, because suppliers don't know where their minerals come from. It should join the electronics industry audit program for conflict-free smelters, and require its suppliers to use only conflict-free smelters. Without that bare minimum, Nintendo is only putting a fig leaf over serious issues of war and slavery (Sasha Lezhnev, cited in Crecente 12 September 2012).

In September 2012 Walk Free protested Nintendo’s New York Wii U event (Crecente 12 September 2012). However, Nintendo’s CSR Procurement Policies still do not say anything about conflict minerals (Nintendo 2016).

III.G. Discussion

Enough never launched a boycott. Instead, its communications steered consumers toward some electronics companies rather than others. In addition to being potentially harmful given the complexity of the problem, a specific boycott call appears to have been unnecessary in this case. After all, “you don’t need to run a boycott to get big brand names on the run; everyone knows what’s on the table. […The Enough Project’s] plan is that just naming and shaming will ratchet up the pressure, and in turn these companies will lean on the smelting operations that supply the minerals they use.” (Bunting 13 December 2010). While not a boycott – campaigners never explicitly called for users to stop purchasing (Sterling 27 February 2011) – Enough did rely on PC as a source of pressure throughout. An interesting dynamic of this has been the use of “name and shame” tactics to induce smelter participation in the third-party audits (Chasan 30 March 2016), coupled with the use of praise to reward companies that acted.

Enough’s practice of rewarding leaders and shaming laggards seems to be part of a strategy to motivate actors to continually push the frontier of action. This strategy is perhaps why experts have noted that “stakeholders from civil society and the private sector have shown willingness to talk and work together” on conflict minerals, in contrast to some other social and environmental issues (Michelle de Cordova, cited in Marlow 13 March 2012). Enough has participated in industry efforts – such as the EICC-GeSI Extractives Working Group – and at times partnered with companies to lobby for legislative change. Enough’s model of research and indirect activism may be another reason that it has been able to collaborate to the extent that it has with companies and government actors. This collaborative dynamic is especially important for a complex global challenge like conflict minerals, where the absence of governance, at the state and international level, is a primary obstacle. Although certainly the conflict minerals movement has had its setbacks and troubles, establishing a collaborative dynamic has resulted in considerable progress since 2007. New modes of governance, such as CFS, US conflict minerals disclosure, iTSCi, and the ICGLR-OECD-UN GoE forum, have been created. Although not an unambiguous success, there is some evidence that the link between conflict and minerals has been severed, at least for the 3Ts, and that company behavior has mattered (Simonson 27 July 2016).

Enough also encouraged the development of in-region conflict-free certification and capacity-building programs, such as CFS, SfH, CFTI, and PPARMT. This approach was perhaps crafted to address criticism that the conflict minerals movement had resulted in an effective mineral boycott in the region, resulting in negative socio-economic effects (Radley 19 April 2016; Meger 31 August 2012; Marlow 13 March 2012). Enough’s approach also suggests a keen understanding of the global nature of the problem and the need to build regulatory systems that shape global value chains. National and international standards like Dodd-Frank s. 1502 and the OECD DDG are components of such systems, but equally important are the norms of buyer-supplier relationships and the use of CSR supports to build local capacity. Without all three of these components developing simultaneously, companies would be able to pass the buck to other actors more defensibly.

Of course, the tripartite nature of the governance challenge requires a lot from companies, which increases the cost to participation. Enough’s approach thus appears to have centered on emboldening “leading” companies to act, by providing a basis for these companies to differentiate themselves. Companies recognized as “leaders” may have been more receptive to taking public stances on upcoming legislation, thus providing Enough leverage in its public politics. Moreover, these “leading” companies often made statements reinforcing their status and, in doing so, reaffirmed expected “good practice” on conflict minerals as it existed at a given time. The self-congratulatory statements of leading companies then made it easier for Enough to claim that progress is possible and companies simply are insufficiently committed.

As the literature predicts, Enough appears to have recognized that it would be all but impossible to target less visible companies. Instead of including these companies in its efforts directly Enough has relied on two mechanisms: legislation and changes in supplier practices through demand from the (targeted) visible firms. Legislation – the “specter of regulation” – is often considered as part of the firm’s calculus in responding to PC campaigns. However, the role of buyer-supplier relations (Locke 2013) is quite often not accommodated for in boycott-buycott studies. We know from the Enough campaign that consumer pressure was essential in prompting not only the decision of electronics firms to ask suppliers to adopt certification programs, but also in the response of smelters themselves. For instance, Malaysia Smelting in Kuala Lumpur is the world’s third-largest producer of tin. It participates in CFS and pays for annual third-party audits with funding from Intel. Its CEO, Chua Cheong Yong, has cited consumer pressure as its reason for acting: “If consumers stop buying materials from the Congo, then people like us have to disengage because we cannot put ourselves in a position where people won’t buy from us” (cited in King 5 June 2014).

Studying a “boycott” or “buycott” campaign on conflict minerals misses all of these aspects of the Enough campaign – most obviously because it was a private political campaign that used PC but it was not a boycott per se. Moreover, a traditional boycott-buycott study would code as separate consumer actions that were in fact part of the broader Enough campaign. This is true, first, in regards to the different activist campaigns that Enough supported through its indirect PC approach. Second, this case shows that the link between private and public political action is essential in complex global challenges like conflict minerals.

IV. The Iterative Dynamics of PC Campaigns

The conflict minerals case study demonstrates that existing studies of PC campaigns, which take as their unit of analysis individual boycott or buycott campaigns, are deficient in several respects: PC campaigns are iterative; inter-firm dynamics are critical to understanding how PC campaigns unfold; and public politics matter.

First, PC campaigns are iterative. Campaigner demands evolved over time in the case study, leading to communication dynamics in which firms were differentiated by their level (and type) of progress and where Enough simultaneously punished some firms in its communications while rewarding others. This suggests that existing theoretical approaches, which view boycott and buycott campaigns as discrete events, obscure the inter-temporal and inter-firm dynamics that are critical to understanding advocacy organizations’ (and firms’) decisions.

An important implication of viewing PC as iterative is how this shapes the justification of advocacy organizations’ demands. As practice develops throughout an iterated PC campaign, the advocacy group need no longer exclusively appeal to what is morally right in an abstract sense. Instead, advocates can justify their demands through appealing to industry norms or frame their role as holding companies accountable to commitments that they have already made. In the Enough Project’s conflict minerals campaign certain practices – like mapping the firm’s supply chain, asking suppliers to demonstrate due diligence, and buying CFS-certified minerals – came to be viewed as expected conduct for responsible electronics companies. In addition to the regularization of certain practices across the industry, public commitments by firms about their own conduct can have an effect. An example outside of the present case is the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights and PC targeting Chevron and British Petroleum (Hofferberth 2011). In these instances, what results may be (in a different sense than Gjølberg (2011) and Buhman (2010) intended) the “emergent juridification” of CSR, as a sense of “binding-ness” is established – that is, there is a shared sense of obligation on which campaigners draw as a basis for future campaigns. Viewing PC campaigns as iterative helps to shed light on the communication dynamics by which a sense of binding-ness is developed – how certain practices come to be viewed as obligatory or required. It also has the potential to connect PPAs to the socialization of business leaders that participate in TBGIs, which may affect corporate strategy in a lasting sense, as suggested by van der Ven (2014).

Viewing PC campaigns as iterative allows us to devote attention to another aspect of private politics: the influence of inter-firm dynamics. As the case illustrates, advocacy groups strategically differentiate companies from one another – designating some as “pioneers” or “leaders” and others as “laggards” – and “leading” firms reinforce this dynamic through self-congratulatory rhetoric and new commitments. Advocacy organizations can also use this dynamic to move the frontier of progress on an issue, by offering new opportunities for “leaders” to consolidate their positions and criticizing leaders that rest on their laurels. Firms also collaborate in response to PC campaigns through industry standards, projects, and advocacy stances. The configuration of these collaborations was not uniform across the industry, as a “greenwashing” perspective might anticipate. Instead, the incidences of collaboration were greatest for “leading” firms, suggesting that this differentiated identity may have played a role in shaping industry dynamics. Attention to the role and structure of “coopetition” (CBN 25 August 2014) in response to PC campaigns would shed further light on the causes and consequences of this phenomenon. In particular, it implies that PPAs may influence whether firms act together to limit their environmental and social commitments or whether “coopetition” dynamics strengthen the content of these commitments.

Another important point that this case study does not explore is the effect of multiple, in some cases simultaneous, PC campaigns on firm strategies. For instance, it is worth considering whether and how the ongoing scandal involving suicides and labor abuses at Apple supplier Foxconn’s factories influenced its approach to conflict minerals (Bilton 18 December 2014; Neate 29 July 2013; Dou 21 August 2016). PC campaigns are iterated, but so are company CSR policies. What is unclear is whether multiple scandals have a zero-sum or ratcheting up effect, and under which circumstances. What, if any, are the spillover effects of PC campaigns?

Finally, public politics are important for understanding how PC campaigns influence complex global challenges like conflict minerals. The Enough Project’s conflict minerals campaign illustrates the link between public and private political actions at the domestic and global levels. Enough explicitly engaged electronics companies as partners in lobbying government, establishing working groups to determine how to regulate conflict mineral due diligence, and in developing capacity-building initiatives to respond to the development challenge embedded within the problem of conflict minerals. This reflects another way in which PC campaigns are iterative. As the communicative dynamic evolves over time it results not only in negotiated “agreement” on the roles and responsibilities of companies in regulating the problem, but also in the implementation of governance systems and modalities that make these responsibilities feasible. This is essential for PC when it addresses a global challenge precisely because these campaigns emerge in response to the reality of there being no single competent authority able to regulate the problem.

Furthermore, the conflict minerals case affirms the important role of the state in shaping the contours of global PC campaigns. This is in line with studies that stress the embeddedness of private governance within state regulatory systems (i.e. Lister 2011). The linkage of public and private politics in Enough’s campaign, particularly regarding US conflict minerals legislation, illustrates the looming relevance of the state even in a case where the absence of sovereignty was at the heart of the governance challenge. While PC was used throughout Enough’s campaign to influence buyer-supplier norms, Enough and other advocacy groups also relied on US legislation to drive action of a broader swathe of firms. Two interesting points arise from this observation. First, we have seen the transnationalization of American law emerge as a leverage point for Enough – which tacitly acknowledged that the coercive power of the state was necessary to shape compliance across all industries using 3TGs. That is, US requirements constituted an attempt to build transnational authority for conflict minerals regulation by making SEC reporting companies responsible for the entire value chain. While the s.1502 experiment may soon end, it offers a glimpse of how the transnationalization of state authority is taking place in response to globalization. Second, the conflict minerals case illustrates how PC is an effective, albeit indirect, tactic of public politics. Studies have found that companies, and especially big companies, have greater access to the state than NGOs (Pekkanen and Smith 2014). Insofar as this is true, a strategy of rewarding leading firms can be interpreted as a tool of public politics. This is true, obviously, when firms make statements about legislation, but also in terms of the effect that firm differentiation may have on the stances that firms then take in undisclosed discussions with government, if firms internalize their position as a “responsible” minerals user.

The Enough Project’s conflict minerals campaign was not a boycott or buycott, but it did involve PC. This case highlights several important aspects of global advocacy campaigns that involve PC. First, it demonstrates the iterative nature of PC tactics, which shape norms of responsibility and make possible firm differentiation. Second, it highlights the critical influence of inter-firm dynamics, including coopetition amongst major electronics producers. Third, it directs attention to the links between public and private politics at the domestic and global levels. These three dimensions are important for understanding the role of PC in constructing regulation across state boundaries and within them, especially where state capacity is lacking.

Bibliography

Africa Review. (10 January 2014). Conflict Minerals Ban in the Great Lakes Region GetsStronger. Africa Review.

Advanced Micro Devices (AMD). (2011). Supplier Responsibility. AMD.

Apple. (2015). Supplier Responsibility 2015 Progress Report. Apple, at http://images.apple.com/supplier-responsibility/pdf/Apple_SR_2015_Progress_Report.pdf.

Apple. (2016). Supplier Responsibility 2016 Progress Report. Apple, at http://images.apple.com/supplier- responsibility/pdf/Apple_SR_2016_Progress_Report.pdf.

Arbogast, Tod. (25 August 2009). Dell, HP, Intel and Motorola Aim to Ensure Mineral Supply Chains are Conflict-free. Dell, at http://en.community.dell.com/dell- blogs/direct2dell/b/direct2dell/archive/2009/08/25/dell-hp-intel-amp-motorola- aim-to-ensure-mineral-supply-chains-are-conflict-free.

Auld, G. & Cashore, B. (2012). The Forest Stewardship Council. In Reed, D., Utting, P. & Mukherjee-Reed. (eds.) Business Regulation and Non-State Actors: Whose Standards? Whose Development? Routledge.

Auld, G., Gulbrandsen, L., McDermott, C. (2008). Certification Schemes and the Impacts on Forests and Forestry. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 33, 187- 211.

Bafilemba, Fidel and Lezhnev, Sasha. (April 2015). Congo’s Conflict Gold Rush: Bringing Gold into the Legal Trade in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Enough Project.

Bafilemba, Fidel, Lezhnev, Sasha, and Zingg-Wimmer. (August 2012). From Congress to Congo: Turning the Tide on Conflict Minerals, Closing Loopholes, and Empowering Mines. The Enough Project, at http://www.enoughproject.org/files/ConflictMinerals_CongoFINAL.pdf.

Bafilemba, Fidel, Mueller, Timo, and Lezhnev, Sasha. (June 2014). The Impact of Dodd- Frank and Conflict Minerals Reforms on the Eastern Congo’s Conflict. The Enough Project.

Baron, David P. (2001). Private Politics. Stanford University Graduate School of Business research paper No. 1689, at https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty- research/working-papers/private-politics.

Baron, D.P. and Diermeier, D. (2007). Strategic Activism and Nonmarket Strategy. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 16, 599-634.

Bartley, Tim and Curtis Child. (2014). Shaming the Corporation: The Social Production of Targets and the Anti-Sweatshop Movement. American Sociological Review 79(4), 653-679.

Bartley, Tim and Curtis Child. (2011). Movements, Markets, and Fields: The Effects of Anti-Sweatshop Campaigns on U.S. Firms, 1993-2000. Social Forces 90(2):425-451.

Berens, G., van Riel, C. & Van Rekom, J. (2007). The CSR-Quality Trade-off: When Can Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Ability Compensate Each Other? Journal of Business Ethics 74(3), 233-252.

Berliner, D. and Prakash, A. (2013). Signaling Environmental Stewardship in the Shadow of Weak Governance: the Global Diffusion of ISO 14001. Law and Society Review 47(2).

Best, Jacqueline and Gheciu, Alexandre. (eds.). (2014). The Return of the Public in Global Governance. NY: Cambridge University Press.

Bhattacharya, C.B., Sen, S. & Korschurn, D. (2008). Using Corporate Social Responsibility to Win the War for Talent. MIT Sloan Management Review 40(2), 36-44.

Bilton, Richard. (18 December 2014). Apple ‘Failing to Protect Chinese Factory Workers’. BBC, at http://www.bbc.com/news/business-30532463.

Birth, G., Illia, L., Lurati, F. & Zamparini, A. (2008). Communicating CSR: Practices Among Switzerland’s Top 300 Companies. Corporate Communications 13(2), 182-196.

Brik, A. B. (2013). Does Socially Responsible Supplier Selection Pay off for Customer Firms? A Cross-Cultural Comparison. Journal of Supply Chain Management 49(3), 66-89.

Bross, Dan. (22 May 2012). Microsoft Response Regarding Global Witness Statement on Dodd Frank 1502. Microsoft, available online at https://business-humanrights.org/en/conflict-peace/conflict-minerals/lobbying-seeking-to-undermine-dodd-frank-conflict-minerals-legislation.

Buhman, Karin. (2010). Reflexive Regulation of CSR to Promote Sustainability: Understanding EU Public-Private Regulation on CSR through the Case of Human Rights. Oslo: University of Oslo, Faculty of Law, Legal Studies Research Paper Series.

Bunting, Madeleine. (13 December 2010). The True Cost of Your Christmas Laptop. The Mail and Guardian.

Business Daily. (10 January 2014). Conflict Minerals Ban in the Great Lakes Region Gets Stronger Despite Resistance. Business Daily.

Business for Social Responsibility (BSR). (May 2010). Conflict Minerals and the Democratic Republic of Congo: Responsible Action in Supply Chains, Government Engagement and Capacity Building. Summary report of the multistakeholder Democratic Republic of Congo Conflict Minerals Forum held 12-13 May 2010 in Washington, D.C.,

https://www.bsr.org/reports/BSR_Conflict_Minerals_and_the_DRC.pdf.

Büthe, T. and Mattli, W. (2011). The New Global Rulers: the Privatization of Regulation in the World Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Callaway, Annie. (16 September 2014). Canada to Vote on Conflict Minerals Legislation, Should Join Support for Mining Reforms and Livelihood Projects in Congo. The Enough Project blog, at http://www.enoughproject.org/blogs/canada-vote- conflict-minerals-legislation-should-join-support-mining-reforms-and-livelihood.

Callaway, Annie. (1 June 2015). Companies Mark Major Benchmark, Support a Conflict- free Minerals Trade in Conflict. The Enough Project blog, at http://www.enoughproject.org/blogs/companies-mark-major-benchmark-support- conflict-free-minerals-trade-congo.

Callaway, Annie. (12 May 2016). Students – Apply Now! Campus Organizer, Enough Project’s Conflict-free Campus Initiative 2016-17. The Enough Project, at http://www.enoughproject.org/blogs/students-apply-now-campus-organizer- enough-projects-conflict-free-campus-initiative-2016-17.

Canadian Fair Trade Network (CFTN). (2013). Briefing Note: Conflict Minerals and the Conflict Minerals Act. CFTN, at http://cftn.ca/campaigns/just- minerals/news/briefing-note-conflict-minerals-and-conflict-minerals-act.

Capriotti, P. & Moreno, Á. (2007). Corporate Citizenship and Public Relations: the Importance and Interactivity of Social Responsibility Issues on Corporate Websites. Public Relations Review 33, 84-91.

Cashore, B., Auld, G. & Newsom, D. (2004). Governing through Markets: Certification and the Emergence of Non-state Authority. New Haven: Yale University Press.

CBN. (25 August 2014). Coopetition: the Better-Together Approach. Canada Business Network blog. Online at http://www.canadabusiness.ca/eng/blog/entry/4768/

Chegar, Verity. (2012). Legislative Drives Towards ESG: Conflict Minerals and Dodd- Frank. In Allianz Global Investors ESG Matters 5.

Conflict-Free Sourcing Initiative. (16 July 2012). Conflict-Free Smelter Program (CFSP) Smelter Introductory Training and Instruction Document. CFSI, at http://www.conflictfreesourcing.org/media/docs/CFSI_CFSP_SmelterIntroductio n_ENG.pdf.